VIDEOGRAPHER: JACOB LANGSTON

JACKSONVILLE, Florida — Teri Sopp’s former self stares down from a wall in Florida’s Fourth Judicial Circuit Public Defender’s Office. The painting, a gift more than a dozen years ago, bears silent witness as she works to free people also frozen in time, serving lifelong sentences for crimes committed before they turned 18.

For one client, she’s arguing reduced culpability because of lead. She expects to argue the same for other clients.

Sopp is the director of the resentencing project for juveniles serving life without parole. Once de rigeur, the Supreme Court has ruled mandatory life without parole for juveniles is unconstitutional. So now all such cases are eligible for resentencing.

Today, Sopp’s working the case of a client serving life for crimes committed when he was 17 in the mid-1990s. One night, he and some others tried to rob a man. The man shot and killed one of the co-conspirators. Sopp’s client was subsequently convicted of armed robbery and murder for his co-conspirator’s death under Florida’s felony murder law.

Sopp described this as common. “Really, the law in Florida allows any case to be … murder,” she said.

Although the youngest, her client’s consecutive life sentences made his the longest sentence. Today only one of his co-conspirators remains in prison.

A light, chilly rain falls outside as Sopp explains the evidence she will present to convince the court that his sentence should be reduced, ideally to time served. Without resentencing, her client, whose name she asked to be withheld to avoid accusations of trying the case in the press, may die in prison. Much of the evidence to reduce his sentence, known as a mitigation package, is familiar to people in the criminal justice field — child abuse, abandonment, poverty and, of course, youth.

Related story: Abused, Often Homeless, Florida Man Got 2 Life Sentences At 17

Lead can affect impulse control, decision making

One argument stands out from the rest: lead poisoning. For much of his youth, the client lived in and around some of Jacksonville’s most contaminated sites.

According to his case file, “He ate crawdads from McCoys Creek when he was homeless. … in the early 1990s, he exclusively drank water from Lonnie C. Miller Park. He slept in the park, which was later closed due to contamination from toxins. He lived half a mile away from 5th and Cleveland Street ash incinerator and he drank water from the contaminated aquifer. He lived a mile away from the Forest Street Incinerator EPA Superfund site.

“It’s all fenced off now.”

Lead poisoning’s deleterious effect on young children’s brain development is thoroughly established. This is largely why the United States banned lead in paints and gasoline in the last quarter of the 20th century. Today lead persists in the environment and older homes and fixtures. Though more commonly associated with the Northeast, Sopp says Jacksonville’s former industrial center is among the state’s most contaminated. The lead poisoning rate here is more than double the statewide rate.

University of Mississippi

Brian Boutwell

Lead contamination has given rise to a cottage industry for civil litigation, but it’s a rare argument in criminal cases, when it can factor into sentencing. That may be changing. Numerous studies have demonstrated a link between childhood lead poisoning and crime, including violent crime such as homicide.

The lead author of one such study, Brian B. Boutwell, associate professor at the University of Mississippi School of Applied Sciences and Medical Center, stressed that while there’s a demonstrated correlation between lead exposure and violence, more research is necessary to determine the significance of the link. “I wouldn’t say we’re there yet,” he said. “… there’s certainly mounting evidence to think of lead having causal impact on behavior.”

Ingesting or breathing the toxic metal at a young age, which is more common among low-income and minority children, can lower intelligence and permanently damage centers of the brain associated with decision-making and impulse control, all of which contribute to the propensity for crime and violence. Yet most people remain largely unaware of the association; and some, among them prosecutors, Sopp said, scoff at the notion that lead poisoning can make someone more likely to commit a crime.

Armed with her client’s history and scientific research, Sopp is trying to establish that he was exposed to lead and that this exposure diminished his 17-year-old brain’s ability to make sound choices, thus reducing his culpability.

This will be the first time she’s presented such evidence in her 43-year legal career.

A lifetime of harm

Humans have used lead for many millennia. As far back as the Roman Empire, there were rumors that the slightly sweet-tasting metal, whose uses then ranged from pipes to dishes to paints and even as an additive for wine, could make you sick.

Early in the last century, scientists began more closely examining lead’s impact, particularly on children. The findings are clear: Lead damages kidneys, bones, blood and brain. The harm is often permanent.

University of Florida

Dr. Jeffrey L. Goldhagen

“It has an impact on IQ. It has an impact on impulsivity. It has an impact on executive function. It has an impact on academic achievement,” said pediatrician Jeffrey Goldhagen, a former Duval County (Florida) Health Department director who implemented the city’s first lead program in the 1990s.

“It has an impact on criminality.”

A peer-reviewed 2015 study of nearly 60,000 children in Chicago found that early childhood lead exposure, even after controlling for factors such as poverty, mother’s education level, low birth rate and race, significantly increased a child’s chance of failing math and reading in the third grade. That year, the Chicago Tribune reported that a map of lead poisoning cases among children under 6 in 1995 looked extremely similar to a map of aggravated assault rates in 2012, when those children were 17 to 22 years old.

Boutwell’s team used the blood tests and addresses of roughly 60,000 Cincinnati children to track the likelihood of lead exposure at the census tract level. They then mapped 15,000 violent crimes by census tract. They found that areas where more children were exposed to lead also had higher violent crime rates.

“With the exception of rape, aggregate blood-lead levels were statistically significant predictors of violent crime at the census tract level,” reported the peer-reviewed study in the Public Library of Science’s PLOS-One publication. The study is archived in the National Institutes of Health.

Boutwell characterized their findings as statistically significant, though he described the correlation between lead poisoning and violent crime as small to moderate. “That’s not to say that it’s unimportant, it just speaks to the nature of how complex behavior is,” he said.

Studies like Boutwell’s and others have led researchers to theorize that lead contributed to the 1980s crime wave. There are fears that children exposed to lead during the Flint, Michigan, water crisis will one day end up in prison.

The science correlating lead poisoning and criminality is clear, Goldhagen says.

Yet some, including people in the legal arena, are skeptical of lead’s effect on criminal behavior. Speaking on background, one mitigation specialist, a physician who advertises expertise in lead poisoning, described it as preposterous. Another said that when lead poisoning is established, prosecutors often offer a plea deal. But doing so can be difficult for cases like Sopp’s client, who grew up in a time when testing was rare and the standard for diagnosing lead poisoning was far higher.

Decades ago, the threshold blood lead level (BLL) to diagnose lead poisoning was 25 micrograms per deciliter (µg/dL). Today it’s five. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) holds that no amount of lead exposure is safe.

There’s no way to know how many people living today were exposed to unsafe levels of lead, as testing was extremely limited and levels now considered poisonous were classified as safe. In 2016, Reuters found that millions of children still go untested.

The more time passes, the more difficult it is to prove lead poisoning. But by examining symptoms, possible sources of exposure and brain scans — lead poisoning in young children often leaves gaps in certain areas of the brain — it may be possible to make a compelling case. That’s what Sopp is hoping to do.

Poison on the walls

If he had to do it all over again, Frank probably never would have bought that home in south Jacksonville. Soon after they moved in in 1980, his wife set about fixing up the 1950s era home. To get old paint off the interior, Frank (name changed to protect his family’s privacy) said she used a technique where paint is heated, stripped and swept or vacuumed up.

The memory bothers him now.

“If that paint had lead in it, it probably was weaponized,” he said.

His first daughter was born several years after they bought the house. Everything seemed fine at first, but as time went by, she fell further behind her peers. Frank says her language and motor skills were stunted; she struggled with impulse control and aggression. He recalled her throwing things — never at people — and smashing her head against walls.

She was eventually diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder and being intellectually disabled, though he believes her IQ is actually higher than that because she struggles to focus.

For years, the family sought answers. Test after test failed to find any reason for her diagnoses. Frank recalls a Pennsylvania children’s hospital giving her a brain scan at one point.

“There were some areas of her brain that were shrunk or not developed,” he said.

Eventually, doctors told them that the cause was either environmental or indeterminable.

Since then, science has established links between lead exposure and all his daughter’s symptoms. Frank theorizes it could have been lead or any number of other things. They may never know for sure.

The family moved out of that home before their second daughter was born. She is neurotypical.

Burden on poor, people of color

By 2015, lead poisoning had largely fallen out of the collective consciousness. Then the Flint, Michigan water crisis exploded in the headlines. By the time the water’s unsafe lead levels became front page news, nearly 30,000 children were exposed.

A government-appointed commission later determined that the crisis was partly caused by systemic racism. If Flint had been wealthier and whiter, the crisis might have never happened.

Flint may be the most famous example of how systemic racism contributes to lead poisoning, but it’s not unique. Nationwide, low-income neighborhoods and racial minorities are more likely to be exposed. The CDC reports that children enrolled in Medicaid, who are disproportionately minorities, “are at the highest risk of being exposed to lead.”

“The impact on [Black] communities was devastating and ignored. Hundreds of millions, from an epidemiological and population perspective. Tens of millions of IQ points lost,” Goldhagen said. “… From my perspective it is an example and among the most pressing examples, of the impact of structural and institutional racism in U.S. history.”

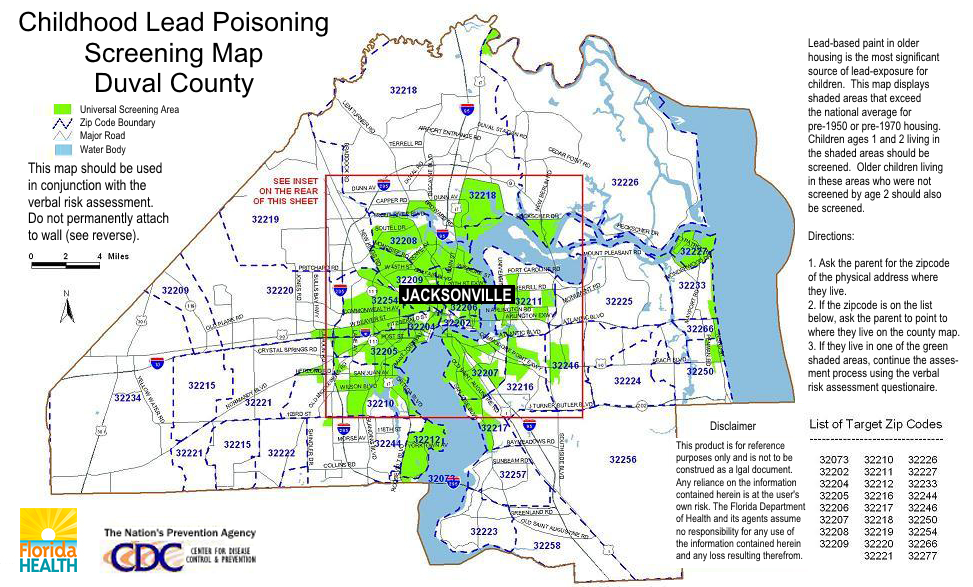

The Florida Department of Health’s childhood lead screening map for Jacksonville shows that most of the city’s majority-Black neighborhoods in the urban core and northwest are in target ZIP codes for lead screening. These areas have homes built before 1960 or 1970, which are far more likely to contain lead-based paint. They also have some of the highest rates of violent crime in a city known as the state’s murder capital.

Florida Department of Health

Lead Poisoning Map, Duval County, Florida

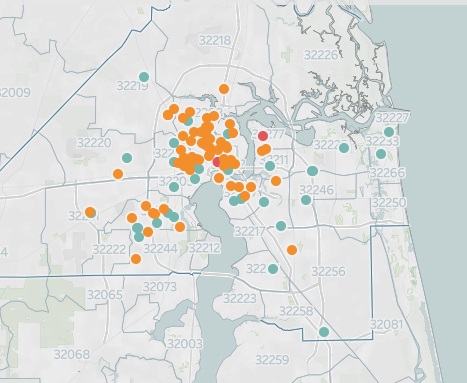

Florida Times-Union

Crime map of Jacksonville, Florida

Many of Sopp’s clients come from these ZIP codes, which also contain the majority of Jacksonville’s dozens of Superfund sites, many of them contaminated with lead. Like the client she’s arguing was exposed to lead, many are Black.

“Many of our clients grew up in that same northwest Jacksonville, same side of town, same poverty-stricken brownfield neighborhoods where all kinds of toxic environs contribute to malformed brain development,” she said.

Why was his blood lead level so high?

Jessica (name changed to protect her son’s privacy) lives in a historic district in the urban core. Her son is enrolled in Medicaid. A year ago, a routine test on her son, then 2, found a BLL of 11 µg/dL, more than twice the threshold deemed a “level for concern” by the CDC. A subsequent blood draw found a BLL of 9 µg/dL.

She was stunned. “I guess I didn’t grow up thinking about that sort of thing. I felt stupid,” she said.

Suspecting paint, one of the most common sources of exposure, she and her husband tested the entire house. The tests were negative, but they took preventative measures anyway.

“We got lead-encapsulating paints and painted all the walls and all the trim and his results weren’t really down,” she said.

In case the lead was in the soil — decades ago many local homeowners and builders used toxic incinerator ash the city gave away as fill dirt — they put down cardboard, mulch and covered it with soil. She also fed him foods rich in nutrients that help pull lead out of the system, like vitamins B, C and E.

His BLL remained stubbornly high. She called the local utility, which provides free lead testing to water customers. It found 6 parts per billion (ppb) of lead, well below the EPA’s actionable level of 15 ppb. (At the height of the crisis, some in Flint had 100 ppb. Ninety percent had above 15 ppb.)

At the same time, she noticed behavioral changes.

“He would get really aggressive sometimes and throw things. I know aggression is a sign of heavy metal,” Jessica said. “I don’t know if he’s upset and doesn’t know how to handle big emotions.”

Jessica searched for answers for months. After reading a paper about bananas possibly having lead in them, she switched to organic bananas for the smoothies she makes him most days.

His most recent blood test showed a 5 µg/dL BLL, which the CDC says is unlikely to cause negative health effects. She and her husband are now talking about selling the house. In the meantime, they’re planning an extended trip in the hope time away detoxes him. They may never find out how he was exposed or how it impacted him, if at all.

“It’s been the unknown that’s been so haunting,” she said.

How children are exposed

Based on the results of a 2005-06 survey, the Department of Housing and Urban Development estimates that as many as 37 million American households have lead paint. The CDC places the number of homes with deteriorated lead paint or lead-contaminated house dust at 24 million, with young children living in 4 million of the most dangerous residences, it estimates.

Children are exposed to lead through paint, household fixtures, parents inadvertently bringing it home from work and in the environment. Young children are more likely to suffer long-term effects because their bodies absorb more lead, they’re more apt to eat things from the ground and put their hands in their mouths and their brains are developing. While Goldhagen agreed that there’s no fixed age at which permanent damage is no longer a risk, the commonly used threshold is 6 years of age or younger, when the brain is rapidly developing.

In parts of Jacksonville, the environment is contaminated with lead from decades past. Some of the city is built on toxic soil.

Being Florida’s industrial center helped Jacksonville thrive in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The industry that contributed to its early success also left behind a toxic legacy in the form of dangerous chemicals and metals. The city is also contaminated by ash that contains lead. Unaware of the risk, the city long offered incinerator ash to residents and builders. Some billed the ash as fertilizer. The city also used this ash as fill dirt on which it built parks, schools and community centers, many in Black neighborhoods. Some operated for decades before the contamination was discovered. Due to toxicity, several remain closed to this day.

Many of Teri Sopp’s clients attended these schools, played in those parks and lived in homes where lead could be on the walls and in the ground.

Jacksonville was largely unaware of the problem until the 1990s when Goldhagen implemented the city’s first lead program, not long after the CDC created its first lead detection program in 1991.

They tested thousands of residents and spent millions cleaning up what they could.

“It became a very significant public health issue,” Goldhagen said. He recalls doing a lot of chelation — a therapy that helps remove lead from blood — on children with dangerously high BLLs.

While ash received much of the publicity, they found that most children were exposed by indoor paint, he said.

Still, the memory of the ash remains imprinted on John Delaney, who was mayor from 1995 to 2003.

“I wasn’t even born when the ash was scattered, but the situation still haunts me,” he said via email.

The city lead program had a measurable impact on reducing lead poisoning and educating the community about the risk. Three decades on, much awareness has faded; like Jessica, many assume lead is a problem from the past.

In recent years, however, the number of Jacksonville residents with unsafe amounts of lead in their blood has quintupled. For years, the city held steady with a few dozen positive tests per year. In 2017, the number leaped from the 30s to more than 150 annually, according to the Florida Department of Health (FDOH).

The local health department couldn’t explain the increase. It said via email that “many factors” may contribute.

Regarding how people are exposed, Chowdhury Bari, the Duval County Health Department epidemiology program administrator, said via email, “This is due mainly to the different sources of lead in the environment and other risk factors.” Risk factors include contaminated water, poverty, living in homes built pre-1978 (when the U.S. banned lead paint), people putting hands or objects into their mouths and family members unknowingly bringing lead dust home from work, he said.

Whatever the cause, lead poisoning is disproportionately high in this coastal city. In 2019, Duval County’s rate per capita was twice that of Florida’s. In the last three years, 150 local children aged 4 or under have been diagnosed with lead poisoning, FDOH reports. Jessica’s son is one of them.

What can be done

While having a child test positive for lead is frightening, testing is part of the solution, as it alerts families to the issue. Jessica knowing about her son’s BLL led her and her husband to take proactive measures to reduce his exposure.

Jessica said their Medicaid insurance, which she believes instigated the initial test, has been extremely helpful throughout.

“They’ve got such a great program,” she said.

For people concerned about lead in the water, the local utility, JEA, offers free testing for customers, as some older homes may have lead pipes or solder. If lead exceeds 15 ppb, per the EPA guidelines, it must work to correct the issue. JEA said that in the last 10 years, it hadn’t found a single case above the EPA action level. (The reporter’s spouse works at JEA.)

The health department also offers resources, such as care coordination, in-home visits and health and nutritional counseling. Goldhagen suggests that remedial programs and academic assistance can help overcome the brain deficits caused by lead exposure in early childhood.

Jacksonville’s legacy of contamination is another matter. Boutwell says that, while overall the country has done a “reasonably good job” at lead cleanup, the potential harm caused by residual lead pollution makes the case for funding further cleanups.

The government was working on developing a federal lead strategy when, in 2018, the Trump Administration abruptly put Ruth Etzel, the EPA’s head of children’s health, on leave. Etzel, who is also a pediatrician, was later permanently removed from her post. The administration said it was based on allegations about her leadership, but numerous colleagues and peers suggested it was actually an attempt to stymie her work, which likely would have recommended increased environmental regulations and cleanups, the New York Times reported. The plans for a federal lead strategy have stalled since then.

The EPA’s work on local Superfund sites is ongoing, albeit slowly, but little else is being done to remove lead from homes in the city. Falling out of the public awareness means there simply isn’t funding or programs for remediation. Although a 2009 analysis found that every dollar spent on lead removal can have an economic benefit of $17 to $220, homeowners are largely on their own — if they know there’s lead, which many don’t. There are laws that require notifying buyers and renters of the potential for lead exposure, but Goldhagen described enforcement as sorely lacking.

For people like Sopp’s client, who’s now in his mid-40s, it’s simply too late to undo the harm. But it might not be too late for that exposure to save him from spending the rest of his life in prison.

Sopp isn’t giving up.

“It’s difficult now. Because of the half-life of lead there’s probably not any indicia in the physiology, you probably couldn’t go and do any blood levels and find lead now because it dissipates over the years,” she said.

“So what you have to look for is proof that there is contact with the lead, exposure to the lead and look at a brain scan and see where it’s left deficits and how the different parts of the brain connect with the other.”

This is the fifth in a Northeast Florida-focused series collaboration between WJCT and the Center for Sustainable Journalism, which publishes Youth Today and the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. This series is part of the Center’s national project on gun violence. Support is provided by The Kendeda Fund. The Center is solely responsible for the content and maintains editorial independence.