VIDEOGRAPHY AND PHOTO: MARCO POGGIO

NEW YORK — They all had disturbing stories, and they all had a familiar ring to them.

Yakov, who declined to give his last name, was waiting in line at the Whitehall Terminal in Manhattan waiting to take a leisurely ferry trip across the bay to Staten Island when he was told to get out by other passengers. He was wearing a mask, he said, but that didn’t matter as much as his conservative garb.

“They’re looking for an excuse to hate us, and they found it in the virus,” the 16-year-old said. “The pandemic has given them the freedom to say what they always have wanted.”

Yehuda Weinstock took his children upstate to go apple picking. “We were treated like we had the plague,” he said. ‘What do you say to your children?”

Coronavirus and the fear it has stoked across the city after bodies were piled up outside hospitals in the spring has led to the resurgence of a social virus. Scarred by daily experiences of anti-Semitism, Hasidic Jews in Brooklyn fear the pandemic and the restrictions that come with it will incite hatred and violence toward them.

Shea Wertz, a 16-year-old, said cameramen from television stations were mocking him when he asked why they were only shooting footage of people not wearing masks and not all of his neighbors, who were. He said it’s part of a trend that has gotten worse as city and state leaders have targeted people like him for fueling a second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I like how he’s [New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio] saying that he loved the Jewish community but he’s still targeting us,” he said.

Asked why he thinks the mayor is picking on the Jews, Wertz turned the question around.

“I would like an answer,” he said. “Anti-Semitism is one.”

They feel singled out

New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo cited a spike in coronavirus cases in four different areas of the city, three of which are home to Hasidic communities, to justify the Oct. 6 closure of schools, businesses and houses of worship.

Orthodox Jews felt officials were singling them out and assaulting their way of life, in what they saw as anti-Semitism gussied up as “common good” politics.

Wertz, a Hasid living in Borough Park, an Orthodox Jewish neighborhood in southwestern Brooklyn, joined an estimated hundreds of other young people in the streets one October evening to protest coronavirus restrictions. There were as many children and teenagers on the street as there were adults, some zooming by on scooters with flashing lights. About half the people in the crowd were wearing masks

The young had passionate feelings about President Donald Trump and what they saw as an effort fueled by anti-Semitism to target their religion. Children pumped Trump election signs in the air and plastered Hebrew Trump bumper stickers to light poles. Wertz and others said there was one thing he felt sure about: Cuomo and de Blasio were hypocrites. At best. At worst, they hated Jews.

Wertz felt particular animosity against the mayor, who in the past represented Borough Park at the City Council and still prides himself on keeping a special relationship with the city’s Orthodox Jewish community.

The atmosphere was part protest and part cultural celebration, but there was an undercurrent of resentment as well. Some members of the crowd turned on reporters. Jacob Kornbluh, a national reporter for the Jewish Insider, was beaten and hospitalized. A mix of visceral anger, folklore and political cabaret transformed, for one night, a peaceful and traditionally religious neighborhood.

Groups of young people gathered produce boxes along 13th Avenue and set them on fire in the middle of the road. Music blasted from speakers placed outdoors.Teenagers broke into dance. Others stood around the fire and watched it burn with righteousness in their eyes.

Familiar scenario with a difference

Many teenagers drew comparisons to the Black Lives Matter protests that rocked the city over the summer. They were responding, they said, to being targeted for being Jews.

“They’re closing the synagogues. It’s the only thing that keeps us together,” said Aron Gravs, 18, who was at the protest with a large group of friends.

A Gadsden flag with the words “Dont Tread on Me” translated into Hebrew flew over people gathered to listen to a local businessman, Harold “Heshy” Tischler, railing against Cuomo and de Blasio with colorful language and insults. His strident voice reverberated from an impromptu stage, while Trump and Thin Blue Line flags turned several city blocks into patches of red and blue. He would later be arrested by police on charges of inciting a riot and unlawful imprisonment in connection with Kornbluh’s incident.

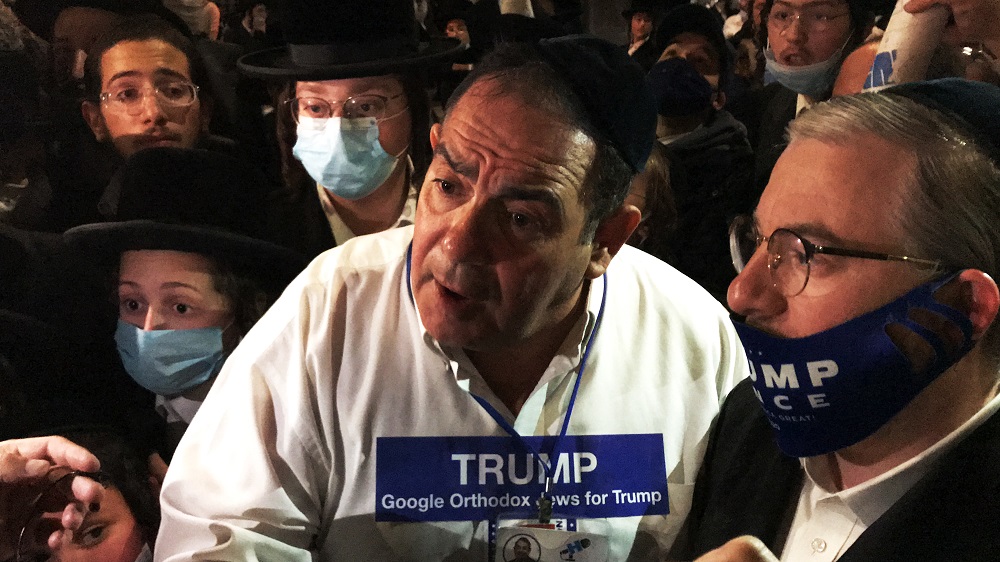

Harold “Heshy” Tischler, a community organizer, spoke at a protest in the Borough Park neighborhood of Brooklyn on Oct. 9. He was later arrested and charged with unlawful imprisonment and inciting a riot for an incident involving a reporter.

Borough Park’s spiral into disorder followed something of a familiar script from around the nation. But teaching online is particularly problematic for this community because they have an aversion to screens for religious reasons. Much of the teaching has been done by phone, which has been disastrous for many parents.

Weinstock said his daughter, who has a speech impediment, had been making great strides before the pandemic. Now her speech has regressed because therapists have not been able to work effectively with her over the phone.

Borough Park transformed into a reservoir of pent-up rage.

“All this violence and all this anger,” said Wertz, who works as a cashier in a grocery store, “you gotta give it out somewhere.”

He lives with his single mother and several siblings, some older, some younger. He lost his cashier job when the lockdown forced the store to close. Like many across the city and the nation, he barely got by, he said.

“We sat six months in our house,” Wertz said. “We were on lockdown. Businesses were closed. The single mothers, the married parents, at home having to deal with the children all day. Nobody’s house was in order. And now, everybody is releasing all their anger. I mean, it’s normal.”

A powerful precedent

A Supreme Court decision from 1905, Jacobson v. Massachusetts, gives state governments ample powers to limit individual liberties during a public health crisis.

The case, which stemmed from a Massachusetts resident challenging compulsory vaccination laws, culminated with upholding the state’s power.

The significance of the ruling is two-fold. It established that a citizen’s individual liberty is not absolute, at the same time creating a legal framework to regulate state power in order to prevent its abuse. The case set a precedent invoked by several other cases related to public welfare later.

Tischler, a self-styled community organizer and the host of a radio show, with a past conviction for immigration fraud, said Cuomo doesn’t have the authority to impose restrictions. He is running for the City Council seat representing Borough Park in the 2021 citywide election.

“Show us the numbers,” Tischler said, referring to Cuomo. “The man is lying, he can’t show anything. Who made him dictator? He’s acting like a child with too much power.

“I’m going to stop him,” he added.

‘Not second time!’

At the Oct. 9 protest in Borough Park, references to Nazi Germany often came up to express the discomfort of a community that feels it’s being scapegoated for the spreading of coronavirus.

A man shouted, “Like the Nazi in 1938. Beautiful. Look at this,” to some TV news crews, lamenting that they focused on people who weren’t wearing face coverings. A tiny 13-year-old boy with a giant hat agreed, shouting: “Germany was only once. Not second time!” in an Eastern European accent. Tischler and a mob of dozens of Hasidic males, many teenagers, surrounded first a Jewish woman talking to a reporter, then a man on the stoop of a house on 48th Street.

She called out some of them for not wearing masks. “If you care about Jews you should wear a mask and respect social distancing. Shame on you,” she said.

The crowd told her to leave: “You shouldn’t have children,” a teenage boy told her. “Why do you hate Jews?” another one said. “What were you doing at a protest with only men?” another boy asked.

Some in the crowd, particularly older people, referenced the Holocaust to articulate their fear over the current pandemic crackdown and the feeling that once again their community is being targeted.

To Wertz and his friends, anti-Semitism is not something abstract based on the collective experience of Jews rooted in the horrors of the past. It’s the posture of government officials in dealing with their community since the pandemic began. The health crisis allowed anti-Jewish bias to manifest, often in form of law enforcement harassment, he said.

“How many times did the sheriffs come to our community when we were on lockdown, and not to other communities. They were harassing us,” Wertz said. “They came down to our community with six cars. They weren’t going to any other communities.”

Announcing the restrictions on Oct. 6, Cuomo acknowledged that the vast majority of the houses of worship that were ordered closed were synagogues.

“I’ve been very close with the Orthodox Jewish community for many years. I understand the imposition this is going to place on them,” Cuomo said then. “I spoke to members of the Orthodox Jewish community today. We had a very good conversation.”

The restrictions, however, spurred immediate backlash, prompting hundreds of Hasidic people to take the streets in Borough Park, culminating with the boisterous early October protests.

Hatred of media

Many of the young men in the crowd expressed distrust for the media for creating a perception that Orthodox Jews are to blame for spikes in coronavirus transmission rates. That perception fuels anti-Semitism, they say.

“The public decides by what they see in the fake news who’s the bad guy. And then they come to us. ‘Oh! It’s the Jews! It’s not China spreading virus!’,” a man who didn’t want to give his name said. “It’s a very evil thing.”

Some youths said they felt oppressed by the presence of reporters in their community in the two weeks leading up to the protest.

As reporters and photographers made their way through the crowd, people screamed, “Fake news!”

“We hate the media,” one of them said.

Many of the people at the protest quoted Trump as their ultimate source of truth.

Several youths said they didn’t believe the infection rates officials gave were real. Others said they believed people from outside their community were getting tested there to boost the numbers of positive cases in order to give state and city officials an excuse to enforce restrictions.

Borough Park went heavily for Trump in 2016.

Several youths said they felt the city and state government are targeting the Orthodox Jewish community because they support Trump. Some of them called it “retribution” or “revenge.”

“Conservatives are pro-life, pro-First Amendment, pro-Second Amendment,” one teenager said. “What are the values of the liberals?”