This story first appeared at The 74, a nonprofit news site covering education.

The ground-breaking charter school is known for small classes, no grades and huge focus on personalization.

![]()

For her senior project at Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School, in Devans. Mass., Katie Collins decided to learn how to play guitar.

She’d originally planned to learn and record four or five songs in eight months, but by early May she told a small crowd, “I chose, in a very Parker fashion, to do two songs, in depth.”

If a school’s ethos can be summed up in a single sentence, that might be it: Less is more. It guides much of what happens in this unusual, if influential, school 30 miles northwest of Boston.

Greg Toppo, The 74

A sign that greets teachers at the entrance to Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School.

“I went into this having slightly unrealistic expectations of myself,” Collins told judges at her presentation, having predicted this time last year that she’d be “a rock star by May.”

Asked whether she considers herself a guitar player yet, she was unequivocal: “My idea of being a guitar player is ‘shredding.’ I’m not there yet.” One day, she said, she’ll be a rock star. “I’m gonna keep at it.”

‘We’re not afraid’

Founded in 1994, Parker is a throwback to a half-century ago, when educators rebelled against the impersonal tyranny of bell schedules and the very idea of letter grades. It has found a way to operate without these, laying the groundwork for some of the most influential school experiments happening today.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Brian Harrigan

Parker students aren’t assigned grades. Instead, they constantly revise their work, which teachers judge on a continuum from “beginning” to “meeting” expectations. Work that fails to pass muster doesn’t receive a traditional D or F. Students simply stay in the “beginning” phase of the process, invited to try again without the traditional consequences lower grades carry in most schools.

“Everyone has chosen to be here. I think that’s important.”

While operating without traditional letter grades presents a challenge for many new students, this problem soon solves itself, said Brian Harrigan, Parker’s head of Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School. By the end of the school year, he no longer hears new students talking about grades. “They are definitely motivated by ‘meets.’”

It seems to be working: Parker boasts an enviable college-going rate of 82.4%. And though it doesn’t offer a single Advanced Placement class, Parker’s pass rate on AP exams is among the highest in Massachusetts.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Deb Merriam

In its latest state report card, Parker’s out-of-school suspension rate was 0.7%. The number of students disciplined for any reason hovered in single digits.

Most schools keep kids in check by threatening lost points or detention if they’re late, forget an assignment or misbehave, said Deb Merriam, Parker’s academic dean and one of three original staff members. “At this school, there’s no sense that there’s something to lose.”

“We don’t do fear.”

There’s also no sense that adults fear kids acting out if they’re unhappy or bored, because so much of the school’s energy is spent ensuring that everyone succeeds in pursuit of their interests.

That principle is central to student life at Parker: Each student owns his or her education.

She added bluntly, “We don’t do fear.”

Roots in Sizer’s work

Ironically, fear played a role in the school’s creation three decades ago.

Parker opened its doors in 1995, a year after Massachusetts approved its charter — one of the first in the state. It was led by a group of parents and teachers inspired by educator Theodore R. Sizer — known to colleagues as Ted — who a decade earlier had written the seminal book Horace’s Compromise: The Dilemma of the American High School.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Sabina Flohr, 13, studies near the entrance to Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School.

The book followed a fictional beleaguered English teacher named Horace Smith, who confronts a system that somehow expects little of students but simultaneously fears their capacity for trouble. The “compromise” of the title describes Horace’s bid to make peace with students by not challenging them too much.

[Related: Native Americans turn to charter schools to reclaim their kids’ education]

Sizer naturally envisioned a more positive and democratic way to run a high school, with teachers becoming trusted coaches rather than simply getting by. He and his wife, Nancy, founded the Coalition of Essential Schools, which worked to spread the word about his ideas, outlined in 10 “common principles” such as “Student as worker, teacher as coach.”

The Sizers were among the school’s founders and served as co-principals from 1998 to 1999. Ted Sizer died in 2009, and the coalition folded in 2016, but many of today’s most innovative high school models — from California’s heralded High Tech High to the national network of Big Picture Learning schools — were founded by his disciples.

‘Is this far enough?’

Individualization is perhaps the key component of what makes Parker work, giving students leeway to build skills and explore interests at their own pace. It also allows teachers to avoid leveling or tracking students, as most schools do.

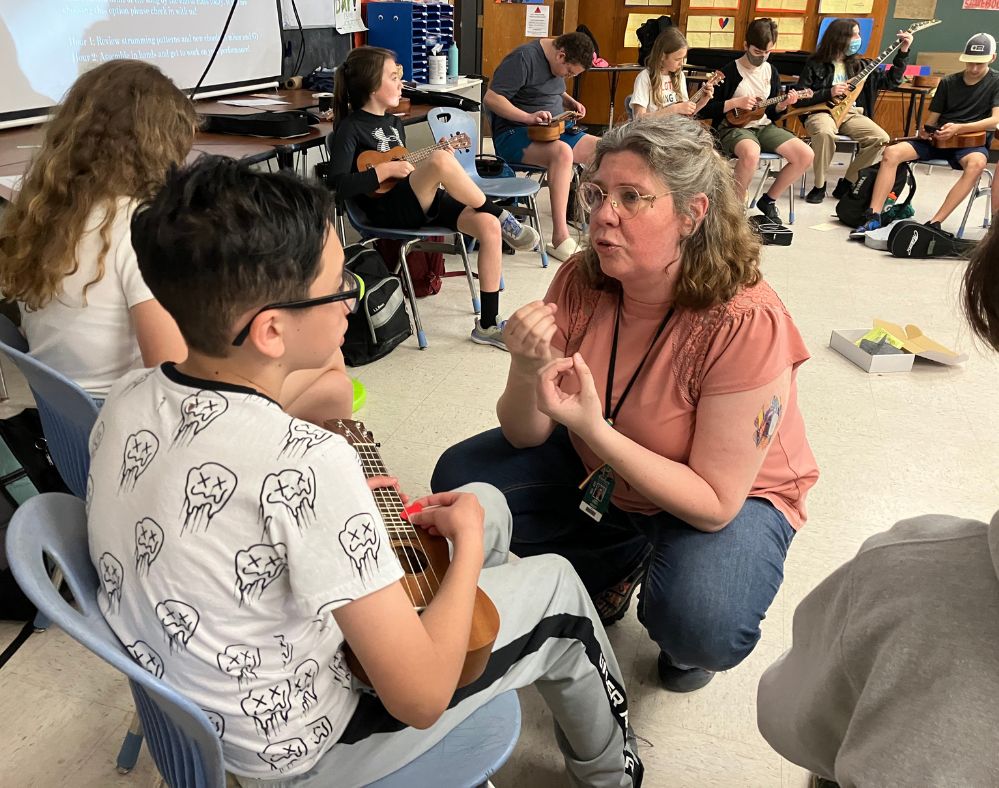

In an Arts and Humanities class one recent morning, students strummed ukuleles in preparation for the day’s lesson: studying and composing protest songs.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Teacher Lucia Starkey works with student Alex Olsen in an Arts and Humanities class.

Within a week of picking up the instruments, they’d be expected to perform a protest song, either a cover of a classic, a new version with different lyrics or an original.

In one of his upper level math classes, teacher Jon Churchill hands students an imaginary $1,000 monthly salary and a handful of bills to pay. Then he tasks them with creating a budgeting spreadsheet.

The push to individualize sometimes makes Churchill think of himself as a sort of mountain guide, forever asking students, “Is this far enough? Is this far enough? What do you want to do? Do you want to go forward?”

A few kids scramble up the mountain, their energy spent making their spreadsheets as efficient and elegant as possible. Others struggle to create the functions needed just to pay one bill. Individualizing the assignment, he said, means “they can all have that same common language, even though the kids are doing slightly different things.”

The key to succeeding in such differentiation, Harrigan said, is class sizes of no more than 20 to 25 students and a commitment to team teaching, especially in the early years.

[Related: At a diversity-focused charter school, worlds of learning for a Black child]

Teachers assigned to Parker’s youngest students co-teach two long, two-hour sessions daily, assessing the work of no more than about 25 students daily, much smaller than the load of most high school teachers, who must often grade upwards of 100 papers per assignment — one Chicago English teacher recently recalled having to grade as many as 170 papers per assignment.

Parker also offers teachers a daily two-hour prep period. That means they can offer “a ton of revision, a ton of reflection” for students to improve their work, Harrigan said.

The school has inevitably inspired broad interest from two groups: homeschoolers and students with special needs. Students with individualized education plans and less restrictive 504 plans now comprise about 40% of Parker’s student body.

“We have a lot of parents whose kids have struggled in traditional districts come here for the support that the school offers,” said Sue Massucco, the arts and humanities domain leader. Parker’s ethos allows students to “come and be yourself,” she said. “If they want to wear a cape to school, they wear a cape to school.”

Senior presentations

Just as they’re spared letter grades, they also attend classes in groups that aren’t strictly age-segregated. Instead, they study sequentially in one of three “divisions,” working at their own pace as they master 13 competencies.

Each division is roughly equivalent to two years, ranging from 7th to 12th grade. Because they “gateway” out of each division, presenting their work to small groups of teachers, parents and classmates, students soon get used to talking to adults, said Marena Cole, a Division 2 arts and humanities teacher. That helps make them more reflective. “They know themselves well,” she said. “They’re asked to reflect on their work constantly, starting from when they’re 12.”

This process culminates in their senior project and a formal, if-friendly, hour-long talk, with 17- and 18-year-olds holding forth on everything they know on topics from hypnosis to van conversion.

Senior Ava Soderman detailed what it’s like to be a ranger at Yellowstone National Park, which she visited last winter. She hopes to work at a national park after she graduates from college — and it shows.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Ava Soderman (left) greets a classmate after her senior presentation on what it’s like to be a park ranger at Yellowstone National Park.

Dressed in a makeshift ranger outfit, Soderman recalled meeting and training with park personnel, persuading one ranger to be her mentor and confronting her doubts about the job.

She admitted that she didn’t quite get around to earning her required emergency medical services and paramedic training.

“If you guys know me, I don’t do well with needles and blood, and I pass out frequently,” she said. “So this is something that I do plan to get my certification in. It’s just going to require a lot of good mindset and good practice.”

Greg Toppo, The 74

Kafi Beckles

The presentations are smart, often funny and deeply personal.

“Everyone has chosen to be here. I think that’s important.”

“By the time they’re seniors, they can hold a room,” said Kafi Beckles, wellness teacher at Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School. “They can present, they can share their opinions, they’re able to have their own thoughts, not just regurgitate facts.”

Less is more

As a lottery-based charter school, Parker serves students from 40 towns in the Boston area. The “essential” in the school’s name means that, as with others guided by Sizer’s ideals, it strives to do just a few things well. Among the coalition’s 10 principles, one of the most often-quoted is: Less is more: depth over coverage.

So there’s no band or football team, no high-tech classroom gear, and no pretense that it can do it all.

The less is more sensibility makes a kind of sense at Parker, which for much of its life has been housed in a repurposed, slightly run-down 1960s-era elementary school on a decommissioned Army base. While Harrigan and others often dream about what life might be like in a newer, nicer building, the idea tends to melt away in favor of discussions about curriculum, teacher feedback and student growth.

But it has occasionally hurt Parker in recruiting, as prospective families inevitably compare it to offerings in their communities.

Greg Toppo, The 74

Pam Gordon

Board chair of Francis W. Parker Charter Essential School and parent Pam Gordon, has had two children attend Parker.

[Related: Why thousands of Philly families are switching to cyber charter school]

She recalled sitting in on town meetings in Harvard, Mass., a few years ago as the town council debated building a new $53 million elementary school. Mold had been discovered in the existing school, which offered a “pretty good reason” to start anew.

“Come over to Parker. The care that’s given to the students, and the way students treat each other — you don’t need a splashy building.”

But when people stood up and said a new building would improve the education there, she said, “I actually laughed.”

She tells people, “Come over to Parker, 10 minutes away, and see what they’re doing, because the education is far superior. And the care that’s given to the students, and the way students treat each other — you don’t need a splashy building.”

***

Greg Toppo is a Senior Writer at The 74 and a journalist with more than 25 years of experience, most of it covering education. He spent 15 years as the national education reporter for USA Today and was most recently a senior editor for Inside Higher Ed. He is also the author of The Game Believes In You: How Digital Play Can Make Our Kids Smarter (St. Martin’s Press, 2015) and co-author, with educator James Tracy, of Running with Robots: The American High School’s Third Century, which looks at automation, AI and the future of high school (2021, MIT Press).

The 74 is a nonprofit news organization covering America’s education system from early childhood through college and career. The 74 is dedicated to examining the issues impacting the education of America’s 74 million children — and the effectiveness of the system that delivers it. The 74 centers their reporting on the teachers, innovators, researchers, school leaders and politicians who shape that education, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. Their mission is to lead an honest, fact-based conversation about how to give American students the skills, support and social mobility they deserve. Backed by data, investigation, and expertise. Sign up for free newsletters from The 74 to get more like this in your inbox.